Industry Spotlight: Water-Energy-Food Nexus

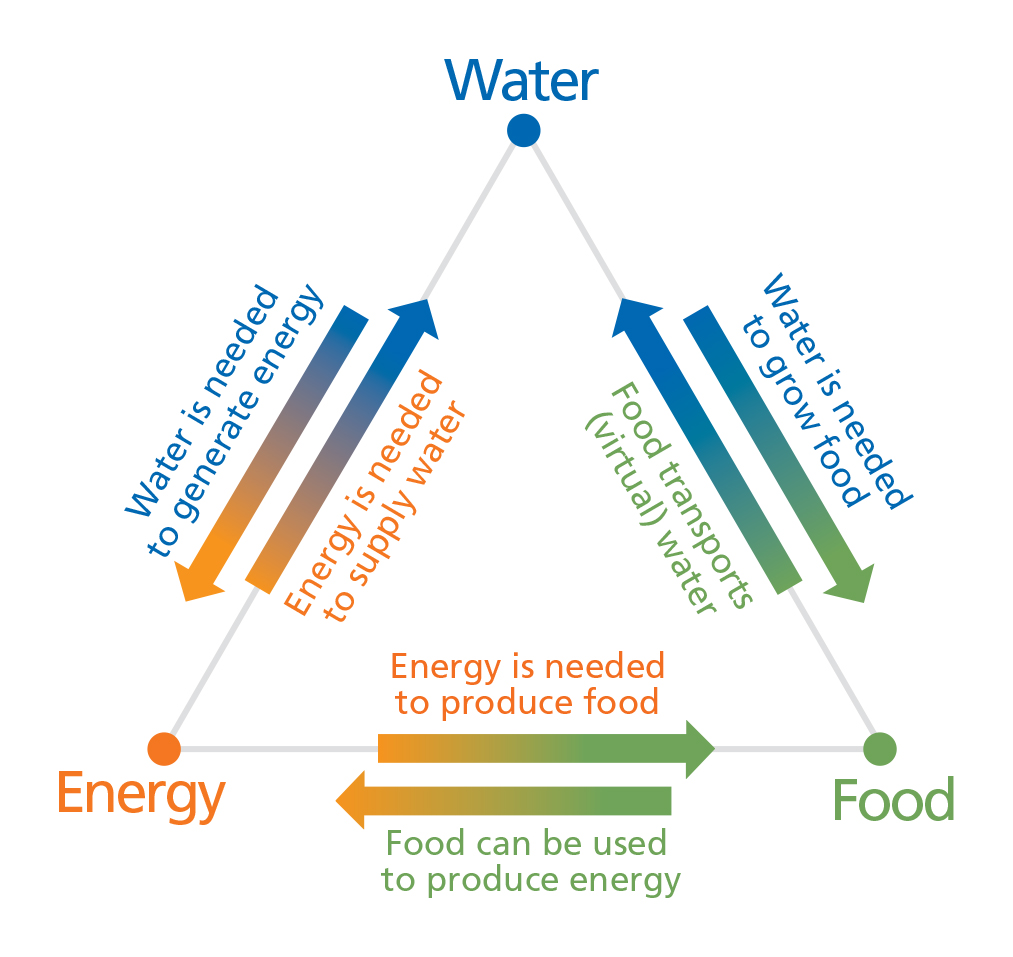

Access to water, energy and food is of critical importance for socioeconomic development, environmental sustainability, improving household livelihoods and ensuring sustainable growth. In addition, the relationship between these three is often referred to as the water, energy and food (WEF) nexus because they have many linkages and interdependencies. For example, food security is affected by accessibility of water to grow crops and energy to process the crops. The importance of the WEF nexus demands an integrated approach in order to manage and develop these three facets of human survival. The WEF nexus is illustrated in the diagram below.Figure 1: Water-Energy-Food Nexus

Source: UNU 2013. Water Security and the Global Water Agenda, United Nations University: Ontario. Available At: https://www.unwater.org/ [Last Accessed: 18 March 2018].

The WEF nexus is particularly important in the SADC region due to socioeconomic vulnerability, varying or extreme weather conditions, and economic dependence on agriculture and mining[31]. For instance, hydroelectric power contributed 99.0% of the electricity supply in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho and Malawi in 2014, which makes water a vital component of both food and energy productions[32]. In addition, these conditions increase competition between the different uses of water which has socioeconomic consequences, i.e. Where countries have varying demand, needs and uses of water resources where one relies more on using it for food production while the other draws out more water for electricity production that takes up more of the resource.

The WEF nexus and cross-sectoral linkages means that poorly coordinated development and management in one sector has the capacity to negatively affect other sectors[33]. It is therefore imperative to find innovative ways to balance competing needs between the WEF sectors to promote socioeconomic development, while at the same time ensuring that development of one sector does not negatively influence the others[34]. The WEF framework is a useful tool to understand the cross-sectoral linkages and develop more effective policies based on this understanding.

Optimal water management supports SADC objectives of poverty reduction, food security, energy security and industrial development[35]. Water is therefore considered to be at the centre of core SADC goals of integration and cooperation. The unequal distribution of water resources is a central challenge amongst other factors prohibiting SADC countries from achieving a well-integrated regional water resource management system, which feeds into food and energy security. Water resources are unequally distributed across the region because most of the region’s water resources are concentrated in shared watercourses which cut across countries with varying social, economic, legal and political conditions[36]. Differences in land governance across member states and the lack of an integrated policy and regulatory framework for the management of water resources makes it difficult for countries to agree on regional water resource management.

Malawi is an extreme case illustrating the importance of the WEF nexus due to its high reliance on groundwater for its food production and energy generation. The Malawian government water management strategy is focused on the Lake Malawi-Shire River System water resources in order to provide water for a number of productive purposes including agriculture, hydroelectricity generation, tourism and urban and rural water supply. Approximately 85.0% of the Malawian population resides in rural areas, with their main activity being agriculture accounting for over 80.0% of employment and accounting for over a third of GDP[37]. As such access to land for arable farming is very important to provide food security for the rural communities. The food sector is the largest consumer of water with approximately 79.0% of water used annually for irrigation[38]. Such a high dependency on water can leave the agriculture activities prone to seasonal changes such as droughts or floods, affecting communities around the river, including the destruction of the much-needed infrastructure. This impacts on the livelihoods of the rural communities highly dependent on agriculture as their main economic activity. Rural transformation should be carried out taking into account the balance between the supply of natural resources and human demand on the environment to promote sustainability.

However, Malawian electricity utility ESCOM is close to meeting its maximum capacity given the little room between national capacity of 326MW and the maximum demand of 330MW in 2017[39]. Malawi’s peak electricity demand is projected to increase to 953MW by 2023. This means that ESCOM will be under pressure to meet demand in future. However, it is unlikely that ESCOM will be able to meet this demand given its low net earnings of USD 10.5 million in 2017[40]. The infrastructure investment gap would far outweigh the income that ESCOM is generating which requires government to intervene. Moreover, Malawi needs to diversify its electricity mix given that hydroelectricity accounts for 95.9% of total existing power stations generation capacity[41].

As a largest land-based water resource in the SADC region, the Zambezi basin is home to about 40.0 million people who rely on the river for drinking water, irrigation, and hydropower production[42]. It is also a source of tourism attraction for tourists coming to see the Victoria Falls, Okavango delta and wildlife living along the river banks[43]. It covers 1.4 million km2, which is about 4.5% of the area of the continent[44]. The Zambezi basin spreads across Angola, Botswana, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. SADC has been tasked with implementing the transboundary water management of the Zambezi amongst its 8 member states. However, the process is challenged by members’ competing water needs, competing interests, differences in human capital and financial resources, as well as weak stakeholder participation[45]. In order to effectively deal with the conflict between human and ecosystem water resource needs, SADC have to consider the impact of both climate change and rural transformation.

The Zambezi basin plays an important socioeconomic role as it provides the communities along the basin with water to generate both energy and for irrigation, as well as the energy needed to supply water and produce food. Therefore, agriculture as the main activity along the basin is boasted for sustainable production, especially for countries like Malawi. For the Zambezi basin as a whole, the water requirements are much less than the water availability. Attention has to be paid, however, to the Chobe tributary, originating in Angola and shared by Angola, Zambia, Namibia and Botswana. The Zambezi River entering Zambia from Angola in the north has an annual discharge of 18 km3, which is twice the volume needed to irrigate the 700,000.0 hectares potential of Angola. The Chobe tributary, however, has a discharge of only 1.3 km3 per year when leaving Angola, so if a large part of the irrigation potential area of 700,000.0 hectares in Angola or if part of the irrigation potential of 159,000.0 hectares in the upper Zambezi basin in Zambia is located in this sub-basin, problems may arise for Namibia and Botswana, even though irrigation potential there is very limited compared to the other countries. Further downstream, no particular problems are expected in terms of water resources[46]. However, water regulation would be necessary for full development of the potential.

The WEF nexus is undoubtedly of key importance for land resource management and rural transformation. Meeting of basic human needs, enabling alternative livelihoods and contributing to national development are all linked to the nexus, particularly in the African context. However, without clear linkages between individual national objectives of SADC member states to regional goals, the relationship between food, water and energy cannot be meaningfully exploited for the sake of rural transformation.

By Grace Nsomba and Michael Andina

[31] Conway, D., van Garderen, E.A., Deryng, D., Dorling, S., Krueger, T., Landman, W., Lankfort, B., Lebel, K., Ringler, C., Thurlow, J., Zhu, T. & Dalin, C. 2015. ‘Climate and Southern Africa’s Water-Energy-Food Nexus’, Nature Climate Change, Vol. 5, pp.: 837–846. Available At: http://dx.doi.org/ [Last Accessed: 24 January 2018].

[32] SAPP 2016. SAPP Statistics 2016, Southern African Power Pool: Harare. Available At: http://www.sapp.co.zw/ [Last Accessed 27 January 2018].

[33] ZWC 2016. Zambezi Today: Water-Energy-Food Nexus Integrated Planning Essential, Zambezi Watercourse Commission: Harare. Available At: http://zambezicommission.org/[Last Accessed: 22 January 2018].

[34] ZWC 2016. Zambezi Today: Water-Energy-Food Nexus Integrated Planning Essential, ibid.

[35] SADC 2006. Regional Water Strategy, Southern African Development Community: Gaborone. Available At: http://www.sadc.int/ [Last Accessed: 23 January 2018].

[36] SADC 2006. Regional Water Strategy, ibid.

[37] IMF 2017. Malawi Economic Development Document, International Monetary Fund: Washington, D.C. Available At: https://www.imf.org/ [Last Accessed: 1 May 2018].

[38] IMF 2017. Malawi Economic Development Document, ibid.

[39] SAPP 2017. SAPP Annual Report 2017, Southern African Power Pool: Harare. Available At: http://www.sapp.co.zw/ [Last Accessed: 15 April 2018].

[40] SAPP 2017. SAPP Annual Report 2017, ibid.

[41] SAPP 2016. SAPP Annual Report 2016, Southern African Power Pool: Harare. Available At: http://www.sapp.co.zw/ [Last Accessed: 15 April 2018].

[42] SADC 2016. Bridging Water Series: Zambezi River Basin, on the Southern Africa Development Community Website, viewed on 15 April 2018, from www.sadc.int/.

[43] SADC 2016. Bridging Water Series: Zambezi River Basin, ibid.

[44] FAO 2016. The Zambezi Basin, on the Food and Agriculture Organisation Website, viewed on 18 April 2018, from http://www.fao.org/.

[45] SADC 2016. Bridging Water Series: Zambezi River Basin, ibid.

[46] FAO 2016. The Zambezi Basin, ibid.